Basics of Hmong Phonology

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Linguistics |

| ✅ Wordcount: 12522 words | ✅ Published: 23rd Sep 2019 |

Hmong is a language that has finite resources. With most of the linguistic studies done in the late ’80s and early ‘90s, there are a limited amount of studies done about the Hmong language. Therefore, as a native speaker myself, much of my resources came from working with other native speakers of Hmong, reading texts about the linguistic structure of tonal languages, using Praat and Hmong textbooks. I hope to further this study of the Hmong language and its’ linguistic features. For my paper, I will be discussing the basic phonology of Hmong, particularly on White Hmong or “Hmoob Dawb”. I will be including the consonant chart, the vowel chart, a syllable structures chart, a tone chart and a Swadesh list comprised of 200 Hmong words.

[KEYWORDS: Hmong, consonants, vowels, syllable structure, tones]

1. INTRODUCTION. Hmong is a language that is closely related to the Miao or Mien language spoken in Southern China (Haudricourt 1991:335). Moreover, people living in these areas gradually adopted phrases and words from the cultures surrounding them, to produce a whole new language known as Hmong. Hmong is a tonal language and attains its’ semantic meanings through its’ lexical categories and word order. Its’ vocabulary consists of monosyllabic words that are paired with a tone attached to the ending of each word. With this is mind, tones are an important aspect of the Hmong language, because they can alter the lexical semantic meanings of consonants and vowels, with just a slight change in aspiration, nasalization, or tone. I will be discussing in further details about these features in Hmong.

If you need assistance with writing your essay, our professional essay writing service is here to help!

Essay Writing Service2. CONSONANTS. White Hmong has twenty-two single consonant sounds as displayed in the pulmonic IPA chart below (Figure 1). Overall, Hmong has roughly fifty-seven consonants which include the two, three and four consonant clusters. However, these clusters are a bundle of the same single-consonants listed here. Thus, it is important that we acknowledge that there are strictly twenty-two sounds on the Hmong Pulmonic Consonant Chart, except for the two affricates ‘ts’ [ʤ] and ‘tx’ [ʦ], which lack manner and place of articulation on the chart.

|

Bilabial |

Labiodental |

Dental |

Alveolar |

Postalveolar |

Retroflex |

Palatal |

Velar |

Uvular |

Pharyngeal |

Glottal |

|

|

Plosive |

p b |

t d |

c |

k |

q |

ʔ |

|||||

|

Nasal |

m |

n |

|||||||||

|

Trill |

|||||||||||

|

Tap/Flap |

ɾ |

||||||||||

|

Fricative |

f v |

s |

ʃ ʒ |

ç |

h |

||||||

|

Lat. Fricative |

|||||||||||

|

Approximant |

j |

||||||||||

|

Lat. Approximant |

l |

Figure 1. Hmong Pulmonic Consonant Chart

As we move further, it is important that we see how an aspiration on a consonant sound is significant in Hmong. Aspiration can change the semantic meaning of a lexical word in Hmong. In a way, Hmong uses aspiration to create a different consonant sound, which can get confusing even for native Hmong speakers. For example, the words ‘tom’ [tɒ ̰̂ʔ] and ‘thom’ [tʰɒ ̰̂ʔ] may look alike in terms of having similar consonants and vowels, but they have two different meanings. The first word ‘tom’ means ‘to bite’ and the second word ‘thom’ means ‘to ask for (information, question, etc.)’. The distinction of aspiration for each word is presented in examples (1) and (2).

(1) Kuv pom nws tom koj.

[kǔ pɒ̰̂ ʔ nɯ̀ tɒ ̰̂ʔ kɒ ʔ]

1SG see 3-SG bite 2SG

‘I see him bite you.’

(2) Kuv thom koj pab.

[kǔ [tʰɒ ̰̂ʔ] kɒ ʔ pá]

1SG to ask for 2SG help

‘I ask for your help.’

Here are more examples of aspiration distinction for contrastive meaning between the words ‘paj’ [pâʔ] which means ‘flower’, and ‘phaj’ [pʰâʔ] which means ‘plate’ shown in examples (3) and (4).

(3) Lub paj loj heev.

[Lù pâʔ lɒʔ hẽ̌]

CLAS. flower big very

‘The flower is very big.’

(4) Lub phaj muaj mov.

[Lù pʰâʔ muâʔ mɒ̌]

2SG plate to have rice

“The plate has rice.’

2.1 CONSONANT CLUSTERS. Originally, the Hmong writing system is based on the widely used Romanized Popular Alphabet (RPA), which aided the Hmong people to develop their own language (Duffy 2007:39). This helped develop the literacy for the Hmong language spoken today. White Hmong or Hmong Dawb has a total of fifty-seven consonants. These include the clusters of two, three, and four consonants in (Figure 2). If we look at the chart, we can see that there are many similarities in how they are structured. The consonant clusters are formed by combining a nasal and an aspiration either before or after the consonant. To explain, two consonant clusters are usually paired with either an aspiration /h/, nasals /m/ and /n/, or laterals /l/. This same rule applies to three-consonant clusters with using either a nasal or an aspiration within the cluster. In contrast, four consonant clusters must include both nasals and aspirations in a cluster.

|

Three Consonant Cluster |

Four Consonant Cluster |

|

|

Ch [cʰ] |

Hml [h+ml] |

Nplh [n+plʰ] |

|

Dh [dʰ] |

Plh [plʰ] |

Ntxh [n+ʦʰ] |

|

Kh [kʰ] |

Tsh [ʤʰ] |

Ntsh [n+ʤʰ] |

|

Hl [h+l] |

Txh [ʦʰ] |

|

|

Hm [h+m] |

Nts [n+ʤ] |

|

|

Hn [h+n] |

Ntx [n+ʦ] |

|

|

Ph [pʰ] |

Hny [h+nj] |

|

|

Qh [qʰ] |

Nch [n+cʰ] |

|

|

Rh [ɾʰ] |

Nkh [n+kʰ] |

|

|

Th [tʰ] |

Nph [n+pʰ] |

|

|

Nc [n+c] |

Nqh [n+qʰ] |

|

|

Nk [n+k] |

Nrh [n+ɾʰ] |

|

|

Np [n+p] |

Nth [n+tʰ] |

|

|

Nq [n+q] |

Npl [n+pl] |

|

|

Nr [n+ɾ] |

||

|

Nt [n+t] |

||

|

Ny [n+j] |

||

|

Pl [p+l] |

||

|

Ml [m+l] |

Figure 2: Hmong Consonant Cluster Chart (Yang 2016: 18)

2.2 PRE-ASPIRATION/POST-ASPIRATION IN CONSONANT CLUSTERS. One key thing to point out is the placement of aspiration either before or after the consonant, which primarily depends on the order of consonants. Now looking back above at (Figure 2), we see that the two consonant cluster column shows aspiration before the cluster as in ‘hl’ [hl], ‘hm’ [hm], and ‘hn’ [hn]. However, if we were to look at three-consonant clusters, we see a random pattern of the placement of aspiration /h/. For example, the clusters ‘hml’ [hml], ‘hny’ [hny] have the aspiration in the front and ‘nkh’ [nkʰ], ‘nch’ [ncʰ] have the /h/ in the back of the cluster. As mentioned earlier, four consonant clusters have both aspiration and nasals. If the aspiration is in the front or initial position, we get aspirations that precede nasals when the consonants are blended together. For example, when we say the word ‘Hmoob’ [hmɒ̃́], we see that the /hm/ consonant cluster sound is mostly produced through our nose and the back of our mouth Aspirations that follow nasals or final position, are when there is an obstruent between the consonant cluster. For example, if the aspiration is in the back, we would say words like ‘khoom’ [kʰɒ ̰̂ʔ] towards the front of our mouth with a slight breathy huff sound. The rule for this example is that the pre-nasalized aspiration is modifying the obstruent. This goes for the four-consonant clusters where /h/ can only follow /n/ when there is an obstruent in between, such as in the word ‘ntshav’ [nʤʰǎ]. In (Figure 2), we see that four-consonant clusters are made by combining an affricate or a single cluster, with a bilabial stop /p/ and a lateral /l/, with a preceding nasal and the aspiration.

3. VOWELS. White Hmong has approximately thirteen vowel sounds, which include short vowels and diphthongs. Surprisingly, Hmong does not have any long vowels. To go into more depth, White Hmong has six short vowels as shown in (Figure 3).

|

[a] ntuǎ |

ntauv |

‘to vomit’ |

|

[e] kě |

ke |

‘path’ |

|

[i] í |

ib |

‘one’ |

|

[ɒ] kʰɒ |

kho |

‘to fix’ |

|

[u] lǔ |

luv |

‘short’ |

|

[ɯ] lɯ |

lws |

‘eggplant’ |

Figure 3. Hmong Short Vowels

The places of articulation are as shown in (Figure 4) below. Vowels ‘a’ [a] has an open sound in the central part of the mouth, ‘e’ [e] has a mid-closed sound in the front of the mouth, ‘I’ [i] has a closed sound in the front of the mouth, ‘o’ [ɒ] has an open sound towards the back of the mouth, ‘u’ [u] and cardinal vowel ‘w’ [ɯ] have a closed sound towards the back of the mouth.

Figure 4. Hmong Vowel Chart (IPA)

Figure 4. Hmong Vowel Chart (IPA)

3.1 DIPHTHONGS. In addition, Hmong vowels also include diphthongs, which combine the vowels into a single vowel. White Hmong has five diphthongs: ‘ai’ [ai], ‘ia’ [ia], ‘au’ [au], ‘ua’ [ua], and ‘aw’ [aɯ]. This combination of two sounds show that the tone of the first vowel is what modifies the second vowel, making the second vowel sound more prominent. For example, we take the vowels ‘a’ + ‘i’ to create ‘ai’ [ai], which sounds the same as the English ‘i’ in words like ‘ice’ or ‘night’. Hmong diphthongs are shown in (Figure 5).

|

[ai] dai |

dai |

‘to hang’ |

|

[ia] ʃiá |

siab |

‘high’ |

|

[au] kʰau |

khau |

‘shoe’ |

|

[ua] cua ʔ |

cuaj |

‘nine’ |

|

[aɯ] kaɯ |

kaw |

‘to close’ |

|

[ẽ] hẽ̌ |

heev |

‘very’ |

|

[ɒ̃] hmɒ̃́ |

hmoob |

‘Hmong’ |

Figure 5. Hmong Diphthongs

4. TONES. Hmong is a tonal language, which means that the words we hear may sound very similar, but due to the distinct levels in pitches; the meanings of the words are very different. For example, in ‘siab’ [ʃiá] (liver); if the ‘b’ tone were changed to ‘v’, we would get the word ‘siav’ [ʃiǎ] (ripen). Hmong has eight different tones, which include ‘b’ a high pitch, ‘m’ a low-falling pitch, ‘j’ a high-falling pitch, ‘v’ a mid-rising pitch, a mid-pitch, ‘s’ a low pitch, ‘g’ a mid-low breathy pitch, and ‘d’ a low-rising pitch. (Yang 2016: 20). As shown in (Figure 6), we can see how a syllable can be combined with different tones to achieve different semantic meanings.

|

Tones |

Romanization |

Translation |

|

tob |

[tɒ́] |

‘deep’ |

|

tom |

[tɒ̰̀̂ʔ] |

‘to bite’ |

|

toj |

[tɒʔ] |

‘hill’ |

|

tov |

[tɒ̌] |

‘to mix’ |

|

to |

[tɒ] |

‘tear’ |

|

tos |

[tɒ̀] |

‘to wait’ |

|

tog |

[tɒ̤] |

‘chair’ |

|

tod |

[tɒ͑] |

‘there, over there’ |

Figure 6. Hmong Tones Chart using [to]

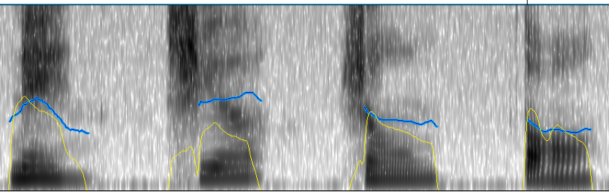

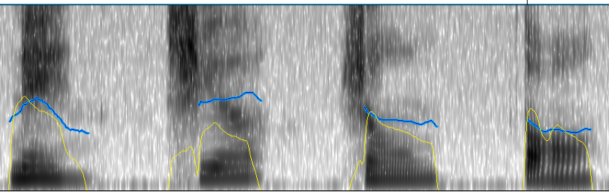

For further analysis, I used Pratt to identify all eight tones and their pitch levels. (Figure 7) shown below are the pitch levels for each level tone and contour tone from these sample words: ‘koj’ [kɒ ʔ], ‘mus’ [mù], ‘luv’ [lǔ], ‘niam’ [nia ̰̂ʔ], ‘neeg’ [nẽ̤], ‘siab’ [ʃiá], ‘zoo’ [zɒ̃], ‘tod’ [tɒ͑].

‘koj’ [kɒ ʔ] ‘mus’ [mù] ‘luv’ [lǔ] ‘niam’ [nia ̰̂ʔ]

neeg’ [nẽ̤] ‘siab’ [ʃiá] ‘zoo’ [zɒ̃] ‘tod’ [tɒ͑]

Figure 7. Hmong Tones (Pitch Spectrogram)

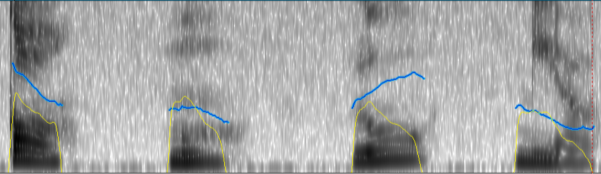

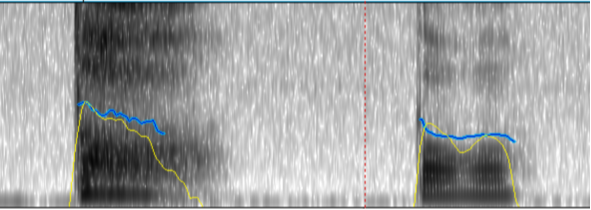

4.1 BREATHY VS. CREAKY TONES. Additionally, Hmong tones include not just falling and rising tones, but breathy and creaky ones as well. Hmong breathy tones change from a high tone to a breathy tone just before changing to a falling tone. This means that the glottal stop does not close all the way, leaving an excessive amount of air flow going out of the mouth. Important to note, the tone ‘g’ cannot be added to an aspirated consonant, or there would be no sound projected. It would only come out as a puff or exhale. In contrast, Hmong creaky tones change from a low tone to falling tone. This means that there is a slight vibration on the vocal cords that compress together, while the glottal stop is restricting airstream. As shown in (Figure 8) below, I used Pratt to show the different pitch patterns of the word ‘tog’ [tɒ̤], a breathy tone, and ‘tom’ [tɒ̰̀̂ʔ], a creaky tone.

‘tog’ [tɒ̤] ‘tom’ [tɒ̰̀̂ʔ]

Figure 8. ‘Tog’ and ‘Tom’ (Pitch Spectrogram)

5. SYLLABLE STRUCTURE. The syllable structure for Hmong is simple. Hmong is monosyllabic meaning it consists of a consonant, a vowel/diphthong, and a tone in romanization form. Many of the words or onsets do not contain any clusters, because their syllables do not contain a coda. The only exceptions are when the consonant is glottalized or nasalized in the coda, especially for tones such as ‘m’ or ‘j’. Therefore, it can vary from one (CVC) to four (CCCCVV) consonants in a row, as shown below in (Figure 9).

|

CCCCVV |

nplʰaí |

nplhaib |

‘ring’ |

|

CCCVV |

nʤʰai |

ntshai |

‘afraid’ |

|

CCVV |

ncɒ |

nco |

‘to miss’ |

|

CVV |

ɾia ̰̂ʔ |

riam |

‘knife’ |

|

CVC |

pí |

pib |

‘to start over’ |

Figure 9. Hmong Syllable Structure Chart

6. CONCLUSION. In the final analysis, we realize how tones are necessary for the context of Hmong words. This is due to the fact that one small change in the ending tone of a word can alter its meaning entirely, as shown in (Figures 7) and (Figure 8). To sum up, consonants, consonant clusters, vowels, diphthongs, aspiration and nasalization are all important lexical and semantic features of Hmong that make up its’ monosyllabic structure.

7. SWADESH LIST: 200 HMONG WORDS

|

|

Rom. Word |

Transcription |

Meaning |

|

Rom. Word |

Transcription |

Meaning |

|

1. |

paus |

/paù/ |

‘fart’ |

101. |

koj |

/kɒ ʔ/ |

‘you’ |

|

2. |

toj |

/tɒ ʔ/ |

‘hill’ |

102. |

moos |

/mɒ̃̀/ |

‘o’clock’ |

|

3. |

haus |

/hau/ |

‘to drink’ |

103. |

nkauj |

/nkaûʔ/ |

‘song’ |

|

4. |

haj |

/ha ʔ/ |

‘even, also’ |

104. |

mob |

/mɒ́/ |

‘to ache’ |

|

5. |

hawv |

/haɯ̌/ |

‘pond’ |

105. |

kws |

/kɯ̀/ |

‘expert’ |

|

6. |

lwv |

/lɯ̌/ |

‘to compete’ |

106. |

peb |

/pé/ |

‘we/us’ |

|

7. |

nplhaib |

/nplʰaí/ |

‘ring’ |

107. |

hnyav |

/hnjǎ/ |

‘heavy’ |

|

8. |

mos |

/mɒ̀/ |

‘soft-hearted’ |

108. |

heev |

/hẽ̌/ |

‘very’ |

|

9. |

siab |

/ʃiá/ |

‘liver’ |

109. |

rau |

/ɾau/ |

‘six’ |

|

10. |

khom |

/kʰɒ/ |

‘to negotiate’ |

110. |

me |

/me/ |

‘small/little’ |

|

11. |

deb |

/dé/ |

‘far’ |

111. |

neej |

/nẽ ʔ/ |

‘life’ |

|

12. |

kaw |

/kaɯ/ |

‘to close’ |

112. |

dib |

/dí/ |

‘melon’ |

|

13. |

liab |

/liá/ |

‘red’ |

113. |

hoob |

/hɒ̃́/ |

‘room’ |

|

14. |

nyeem |

/njẽ ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘to read’ |

114. |

qhiav |

/qʰiǎ/ |

‘ginger’ |

|

15. |

khau |

/kʰau/ |

‘shoe’ |

115. |

kua |

/kua/ |

‘liquid’ |

|

16. |

yug |

/jṳ/ |

‘to give birth’ |

116. |

miv |

/mǐ/ |

‘cat’ |

|

17. |

npawg |

/npaɯ̤/ |

‘cousin’ |

117. |

coj |

/cɒ ʔ/ |

‘to take’ |

|

18. |

daj |

/dá ʔ/ |

‘yellow’ |

118. |

dub |

/dú/ |

‘black’ |

|

19. |

cub |

/cú/ |

‘to steam’ |

119. |

nug |

/nṳ/ |

‘to ask’ |

|

20. |

diaj |

/dia ʔ/ |

‘paddy/field’ |

120. |

yawg |

/jaɯ̤/ |

‘grandpa’ |

|

21. |

taub |

/taú/ |

‘pumpkin’ |

121. |

zoo |

/zɒ̃/ |

‘good’ |

|

22. |

haiv |

/haí/ |

‘nationality’ |

122. |

nkees |

/nkẽ̀/ |

‘tired’ |

|

23. |

paub |

/paú/ |

‘to know’ |

123. |

hais |

/haì/ |

‘to say’ |

|

24. |

npe |

/npe/ |

‘first name’ |

124. |

kub |

/kú/ |

‘hot’ |

|

25. |

dawb |

/daɯ́/ |

‘white’ |

125. |

liam |

/lia ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘to accuse’ |

|

26. |

kawm |

/kaɯ̰̂ ʔ/ |

‘to learn’ |

126. |

siab |

/ʃiá/ |

‘high’ |

|

27. |

nplooj |

/nplɒ̃ ʔ/ |

‘leaf’ |

127. |

tawb |

/taɯ́/ |

‘basket’ |

|

28. |

fwj |

/fɯ ʔ/ |

‘bottle’ |

128. |

sawv |

/ʃaɯ̌/ |

‘wake up’ |

|

29. |

ntsua |

/nʤuà/ |

‘classifier’ |

129. |

nqa |

/nqa/ |

‘to carry’ |

|

30. |

lawv |

/laɯ̌/ |

‘they’ |

130. |

paub |

/paú/ |

‘to know’ |

|

31. |

ntsuj |

/nʤu ʔ/ |

‘spirit’ |

131. |

luv |

/lǔ/ |

‘car’ |

|

32. |

tawv |

/taɯ̌/ |

‘skin’ |

132. |

hu |

/hu/ |

‘to call’ |

|

33. |

nti |

/nti ̰̂/ |

‘to move’ |

133. |

pam |

/pâ̰ ʔ/ |

‘blanket’ |

|

34. |

txiv |

/ʦǐ/ |

‘father’ |

134. |

npiv |

/npǐ/ |

‘pen’ |

|

35. |

dhia |

/dʰia/ |

‘to jump’ |

135. |

laug |

/laṳ/ |

‘left’ |

|

36. |

zeb |

/ʒé/ |

‘stone’ |

136. |

ntev |

/ntě/ |

‘long’ |

|

37. |

ntshai |

/nʤʰai/ |

‘to be afraid’ |

137. |

thoob |

/thɒ̃́/ |

‘bucket’ |

|

38. |

sov |

/ʃɒ̌/ |

‘warm’ |

138. |

tsw |

/tsɯ/ |

‘to smell’ |

|

39. |

hli |

/hli/ |

‘moon’ |

139. |

hnub |

/hnú/ |

‘sun/day’ |

|

40. |

puag |

/pua̤/ |

‘to hold’ |

140. |

hom |

/hɒ̰̌̂ʔ/ |

‘type of’ |

|

41. |

ntuj |

/ntu ʔ/ |

‘sky’ |

141. |

tiab |

/tiá/ |

‘skirt’ |

|

42. |

looj |

/lɒ̃́ ʔ/ |

‘to put on’ |

142. |

vaj |

/va ʔ/ |

‘garden’ |

|

43. |

dhau |

/dʰau/ |

‘over’ |

143. |

dev |

/dě/ |

‘dog’ |

|

44. |

ntsaum |

/nʤau ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘ant’ |

144. |

nyob |

/njɒ́/ |

‘to live’ |

|

45. |

tsev |

/ʤě/ |

‘house’ |

145. |

thov |

/tʰɒ̌/ |

‘to beg’ |

|

46. |

haus |

/haù/ |

‘to drink’ |

146. |

xim |

/si ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘color’ |

|

47. |

nws |

/nɯ̀/ |

‘he/she/it’ |

147. |

lab |

/lá/ |

‘restaurant’ |

|

48. |

lawv |

/laɯ̌/ |

‘to follow’ |

148. |

kawg |

/kaɯ̤/ |

‘end’ |

|

49. |

thaum |

/tʰau ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘when’ |

149. |

dos |

/dɒ̀/ |

‘green onion’ |

|

50. |

ntsia |

/nʤia/ |

‘to watch’ |

150. |

faib |

/faí/ |

‘to share’ |

|

51. |

ntaub |

/ntaú/ |

‘fabric’ |

151. |

laus |

/laù/ |

‘old’ |

|

52. |

luav |

/luǎ/ |

‘rabbit’ |

152. |

ntaiv |

/ntaǐ/ |

‘stairs’ |

|

53. |

ua |

/ua/ |

‘to make’ |

153. |

nrab |

/nɾá/ |

‘middle’ |

|

54. |

luv |

/lǔ/ |

‘car’ |

154. |

pais |

/paì/ |

‘to go’ |

|

55. |

npua |

/npua/ |

‘pig’ |

155. |

pa |

/pa/ |

‘breath’ |

|

56. |

txiv |

/ʦǐ/ |

‘father’ |

156. |

haum |

/hau ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘to fit’ |

|

57. |

kib |

/kí/ |

‘to fry’ |

157. |

mob |

/mɒ́/ |

‘illness’ |

|

58. |

plas |

/plà/ |

‘owl’ |

158. |

tog |

/to̤/ |

‘chair’ |

|

59. |

khoom |

/kʰɒ ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘item’ |

159. |

yuav |

/juǎ/ |

‘to buy’ |

|

60. |

muam |

/mua ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘sister’ |

160. |

nplaig |

/nplai̤/ |

‘tongue’ |

|

61. |

nqhis |

/nqʰì/ |

‘to crave’ |

161. |

cuaj |

/cua ʔ/ |

‘nine’ |

|

62. |

cev |

/cě/ |

‘body’ |

162. |

ntuav |

/ntuǎ/ |

‘to vomit’ |

|

63. |

tog |

/to̤/ |

‘chair’ |

163. |

siv |

/ʃǐ/ |

‘belt’ |

|

64. |

caw |

/caɯ/ |

‘to invite’ |

164. |

tsawg |

/ʤaɯ̤/ |

‘few’ |

|

65. |

kab |

/ká/ |

‘insect’ |

165. |

muaj |

/muâʔ/ |

‘to have’ |

|

66. |

hnia |

/hnia/ |

‘to smell’ |

166. |

kos |

/kɒ̀/ |

‘to draw’ |

|

67. |

riam |

/ɾia ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘knife’ |

167. |

hu |

/hu/ |

‘to address’ |

|

68. |

cuaj |

/cua ʔ/ |

‘nine’ |

168. |

hauv |

/haǔ/ |

‘inside’ |

|

69. |

lwv |

/lɯ̌/ |

‘to erase’ |

169. |

kab |

/ká/ |

‘insect’ |

|

70. |

hniav |

/hniǎ/ |

‘tooth’ |

170. |

ntxiv |

/ntxǐ/ |

‘to add’ |

|

71. |

rho |

/ɾʰɒ/ |

‘to tear off’ |

171. |

nej |

/nêʔ/ |

‘you guys’ |

|

72. |

kov |

/kɒ̌/ |

‘to touch’ |

172. |

niam |

/nia ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘mother’ |

|

73. |

muag |

/mua̤/ |

‘to sell’ |

173. |

luv |

/lǔ/ |

‘short’ |

|

74. |

hnoos |

/hnɒ̃̀/ |

‘cough’ |

174. |

lus |

/lù/ |

‘word’ |

|

75. |

ncig |

/nci̤/ |

‘to travel’ |

175. |

raj |

/ɾâʔ/ |

‘flute’ |

|

76. |

pib |

/pí/ |

‘to start’ |

176. |

nruas |

/nɾuà/ |

‘drum’ |

|

77. |

nrog |

/nɾɒ̤/ |

‘with’ |

177. |

sau |

/ʃau/ |

‘to write’ |

|

78. |

neb |

/né/ |

‘you two’ |

178. |

chav |

/cʰǎ/ |

‘room’ |

|

79. |

nkoj |

/nkɒ ʔ/ |

‘boat’ |

179. |

menyuam |

/me-njua ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘children’ |

|

80. |

khw |

/kʰɯ/ |

‘market’ |

180. |

pog |

/pɒ̤/ |

‘grandma’ |

|

81. |

caum |

/cau ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘to pursuit’ |

181. |

nkag |

/nka̤/ |

‘to go in’ |

|

82. |

hlob |

/hlɒ́/ |

‘elder’ |

182. |

xyab |

/çá/ |

‘incense’ |

|

83. |

nas |

/nà/ |

‘mouse’ |

183. |

dua |

/dua/ |

‘again’ |

|

84. |

ci |

/ci/ |

‘to grill’ |

184. |

phem |

/pʰe ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘bad’ |

|

85. |

pw |

/pɯ/ |

‘to sleep’ |

185. |

huab |

/huá/ |

‘cloud’ |

|

86. |

mov |

/mɒ̌/ |

‘rice’ |

186. |

neeg |

/nẽ̤/ |

‘human’ |

|

87. |

phom |

/pʰɒ ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘gun’ |

187. |

pauv |

/paǔ/ |

‘to change’ |

|

88. |

mus |

/mù/ |

‘to go’ |

188. |

su |

/ʃu/ |

‘lunch’ |

|

89. |

nrhiav |

/nɾʰiǎ/ |

‘to search’ |

189. |

nyuab |

/njuá/ |

‘difficult’ |

|

90. |

pab |

/pá/ |

‘to help’ |

190. |

piav |

/piǎ/ |

‘to narrate’ |

|

91. |

ntxhais |

/nʦʰaì/ |

‘daughter’ |

191. |

nquab |

/nquá/ |

‘pigeon’ |

|

92. |

nco |

/ncɒ/ |

‘to miss’ |

192. |

ntshav |

/nʤʰǎ/ |

‘blood’ |

|

93. |

kam |

/ka ̰̂ʔ/ |

‘to permit’ |

193. |

nkawv |

/nkaɯ̌/ |

‘them both’ |

|

94. |

hnab |

/hná/ |

‘bag’ |

194. |

hom |

/hɒ̰̌̂ʔ/ |

‘type of’ |

|

95. |

muab |

/muá/ |

‘to give’ |

195. |

kwv tij |

/kw̌-ti ʔ/ |

‘brothers’ |

|

96. |

nqaij |

/nqaîʔ/ |

‘meat’ |

196. |

kaij |

/kaîʔ/ |

‘to copy’ |

|

97. |

chim |

/cʰḭ̂ ʔ/ |

‘angry’ |

197. |

phaj |

/pʰâʔ/ |

‘generation’ |

|

98. |

muag |

/mua̤/ |

‘to sell’ |

198. |

ncho pas |

/ncʰɒ-pà/ |

‘to smoke’ |

|

99. |

ceev |

/cẽ̌/ |

‘fast’ |

199. |

luag |

/lua̤/ |

‘to laugh’ |

|

100. |

paj |

/pâʔ/ |

‘flower’ |

200. |

tsov |

/ʤɒ̌/ |

‘tiger’ |

REFERENCES

- Duffy, M.. Writing from These Roots. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2007. Project MUSE.

- Gussenhoven, Carlos and Ebrary, Inc. The Phonology of Tone and Intonation. Cambridge; New York, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Haudricourt, André G., and David Strecker. “Hmong-Mien (Miao-Yao) Loans in Chinese.” T’oung Pao, vol. 77, no. 4/5, 1991, pp. 335–341. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4528539.

- Yang, Kao-Ly. Speaking Hmoob Hais Lus Hmoob. California State University, Fresno. 2016.

APPENDICES

Figure 1. Hmong Consonant Pulmonic Chart [pg. 2]

|

|

Bilabial |

Labiodental |

Dental |

Alveolar |

Postalveolar |

Retroflex |

Palatal |

Velar |

Uvular |

Pharyngeal |

Glottal |

|

Plosive |

p b |

t d |

c |

k |

q |

ʔ |

|||||

|

Nasal |

m |

n |

|||||||||

|

Trill |

|||||||||||

|

Tap/Flap |

ɾ |

||||||||||

|

Fricative |

f v |

s |

ʃ ʒ |

ç |

h |

||||||

|

Lat. Fricative |

|||||||||||

|

Approximant |

j |

||||||||||

|

Lat. Approximant |

l |

Figure 2. Hmong Consonant Cluster Chart (Yang 2016: 18) [pgs. 3-4]

|

Two Consonant Cluster |

Three Consonant Cluster |

Four Consonant Cluster |

|

Ch [cʰ] |

Hml [h+ml] |

Nplh [n+plʰ] |

|

Dh [dʰ] |

Plh [plʰ] |

Ntxh [n+ʦʰ] |

|

Kh [kʰ] |

Tsh [ʤʰ] |

Ntsh [n+ʤʰ] |

|

Hl [h+l] |

Txh [ʦʰ] |

|

|

Hm [h+m] |

Nts [n+ʤ] |

|

|

Hn [h+n] |

Ntx [n+ʦ] |

|

|

Ph [pʰ] |

Hny [h+nj] |

|

|

Qh [qʰ] |

Nch [n+cʰ] |

|

|

Rh [ɾʰ] |

Nkh [n+kʰ] |

|

|

Th [tʰ] |

Nph [n+pʰ] |

|

|

Nc [n+c] |

Nqh [n+qʰ] |

|

|

Nk [n+k] |

Nrh [n+ɾʰ] |

|

|

Np [n+p] |

Nth [n+tʰ] |

|

|

Nq [n+q] |

Npl [n+pl] |

|

|

Nr [n+ɾ] |

||

|

Nt [n+t] |

||

|

Ny [n+j] |

||

|

Pl [p+l] |

||

|

Ml [m+l] |

Figure 3. Hmong Short Vowels [pg. 5]

|

[a] ntuǎ |

ntauv |

‘to vomit’ |

|

[e] kě |

ke |

‘path’ |

|

[i] í |

ib |

‘one’ |

|

[ɒ] kʰɒ |

kho |

‘to fix’ |

|

[u] lǔ |

luv |

‘short’ |

|

[ɯ] lɯ |

lws |

‘eggplant’ |

Figure 4. Hmong Vowel Chart (IPA) [pg. 5]

Figure 5. Hmong Diphthongs [pg. 6]

|

[ai] dai |

dai |

‘to hang’ |

|

[ia] ʃiá |

siab |

‘high’ |

|

[au] kʰau |

khau |

‘shoe’ |

|

[ua] cua ʔ |

cuaj |

‘nine’ |

|

[aɯ] kaɯ |

kaw |

‘to close’ |

|

[ẽ] hẽ̌ |

heev |

‘very’ |

|

[ɒ̃] hmɒ̃́ |

hmoob |

‘Hmong’ |

Figure 6. Hmong Tones Chart using ‘to’ [pg. 6]

|

Tones |

Romanization |

Translation |

|

tob |

[tɒ́] |

‘deep’ |

|

tom |

[tɒ̰̀̂ʔ] |

‘to bite’ |

|

toj |

[tɒʔ] |

‘hill’ |

|

tov |

[tɒ̌] |

‘to mix’ |

|

to |

[tɒ] |

‘tear’ |

|

tos |

[tɒ̀] |

‘to wait’ |

|

tog |

[tɒ̤] |

‘chair’ |

|

tod |

[tɒ͑] |

‘there, over there’ |

Figure 7. Hmong Tones (Pitch Spectrogram) [pg. 7]

‘koj’ [kɒ ʔ] ‘mus’ [mù] ‘luv’ [lǔ] ‘niam’ [nia ̰̂ʔ]

neeg’ [nẽ̤] ‘siab’ [ʃiá] ‘zoo’ [zɒ̃] ‘tod’ [tɒ͑]

Figure 8. Figure 7. ‘Tog’ and ‘Tom’ (Pitch Spectrogram) [pg. 8]

‘tog’ [tɒ̤] ‘tom’ [tɒ̰̀̂ʔ]

Figure 9. Hmong Syllable Structure Chart [pg. 9]

|

CCCCVV |

nplʰaí |

nplhaib |

‘ring’ |

|

CCCVV |

nʤʰai |

ntshai |

‘afraid’ |

|

CCVV |

ncɒ |

nco |

‘to miss’ |

|

CVV |

ɾia ̰̂ʔ |

riam |

‘knife’ |

|

CVC |

pí |

pib |

‘to start over’ |

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please:

GBR

GBR